Waste-to-chemicals wordt waste-to-jet

Duurzame vliegtuigbrandstof

Het ‘waste-to-chemicals’-project in Rotterdam slaat een nieuwe koers in. De beoogde fabriek gaat geen duurzame methanol, maar duurzame vliegtuigbrandstof produceren. Hiervoor wordt een reactor-sectie in het ontwerp van de installatie vervangen. Het consortium continueert met Enerkem, Shell en het Havenbedrijf Rotterdam als deelnemers. “De markt voor vliegtuigbrandstoffen is voor dit project relatief zekerder en beter. Minder risicovol dus.”

In oktober 2016 presenteerde een consortium [zie onder, red.] het plan om in de Botlek een ‘waste-to-chemicals’-fabriek te bouwen, die duurzame methanol uit afval zou gaan produceren. “De afgelopen jaren hebben wij benut om de business case meer robuust te maken en verder te ontwikkelen”, zegt Nico van Dooren, director new business development bij het Havenbedrijf Rotterdam, een van de deelnemers aan het consortium. “Er is onderzocht welke rol de partners spelen, wat de meest optimale locatie van de plant is en welke infrastructuur er nodig is. Tegelijk liep de ontwikkeling van de technologie door en werd de business case verder geanalyseerd.”

‘Groene infrastructuur’

Shell trad in 2019 tot het waste-to-chemicals-consortium toe. “Shell heeft als doelstelling om de hele business te decarboniseren”, licht Andries Boon toe, teamleider bij Shell voor biobrandstoffenontwikkeling in Europa. “Bovendien bieden infrastructuur zoals Porthos, het warmtenet, electrolysers en de waterstofbackbone synergie met dit soort projecten. We hebben immers stroom en waterstof nodig, en maken CO2. Dan is het een voordeel op groene infrastructuur te kunnen aansluiten. Die mogelijkheid maakt het Rotterdamse industriële cluster voor ons aantrekkelijk.”

Koerswijziging

Nu blijkt dat er een belangrijke koerswijziging wordt ingezet. “We hebben het project tegen het licht gehouden”, zegt Boon. “Tachtig tot negentig procent ziet er goed uit. Alleen is de markt voor methanol in vergelijking minder diep. Het is lastig om daar een eerste project op te baseren. Verder wordt de toepassing van duurzame methanol in de biochemie minder gestimuleerd door de huidige regelgeving.”

Waste-to-jet

In plaats van methanol zal de fabriek duurzame vliegtuigbrandstof gaan produceren. Boon: “Afval is de perfecte grondstof om op lange termijn vliegtuigbrandstof van te maken. Er zijn weinig alternatieven. Vliegtuigen zullen niet zo snel op waterstof of elektriciteit gaan vliegen. Je zit dus vast aan een vloeistof als brandstof. Waste is daarvoor een uitstekende grondstof. Zo creëer je een houdbare business case voor de lange termijn. De vliegtuigindustrie staat in de spotlights om te decarboniseren. Hiermee helpen wij luchtvaartmaatschappijen en vliegvelden hun carbon footprint te verlagen. Voor ons is het een veilige markt voor een eerste fabriek met best veel risico.”

Kralensnoer

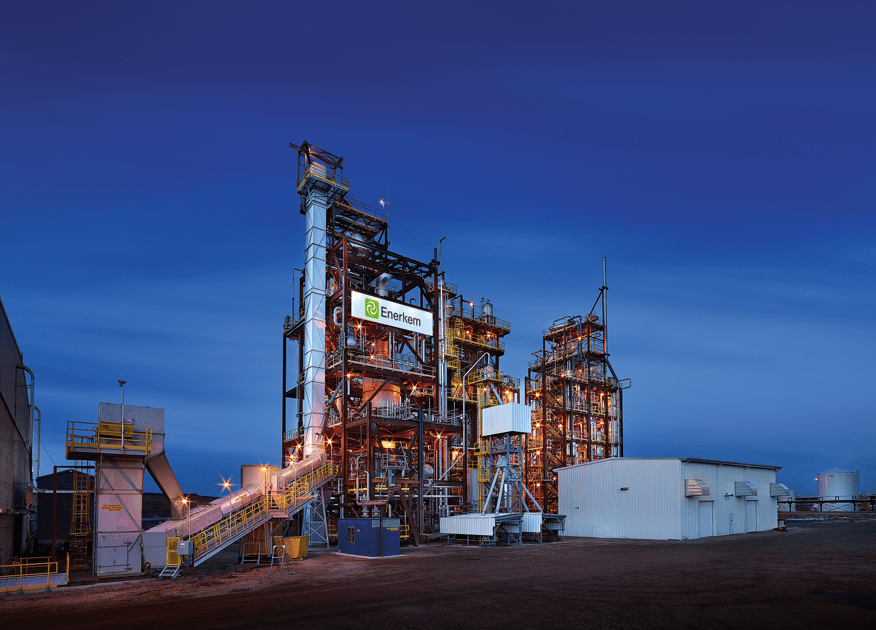

De omslag heeft vooral betrekking op de afzetmarkt, en in mindere mate op het ontwerp van de fabriek, benadrukken Van Dooren en Boon. “Tachtig procent van de fabriek blijft gelijk”, legt Boon uit. “Afvalstromen als voedsel, hout en verpakkingsmateriaal met plastic breken wij af tot syngas, dat uit waterstof en koolmonoxide bestaat. Dat is hetzelfde als oorspronkelijk was gepland. Alleen hangen wij de koolmonoxide niet in één keer aan waterstof om methanol te maken, maar wij rijgen er een kralensnoer van met een langere keten van koolstoffen. Dat is een typische vliegtuigbrandstof. Daarvoor wordt aan de achterkant van de fabriek een reactor geplaatst. Shell maakt al tientallen jaren gebruik van deze Gas-to-Liquid-technologie. In Maleisië en Qatar wordt die op grote schaal ingezet.” Volgens Boon kun je niet spreken van een volledig nieuw concept. “Tachtig procent van de fabriek is een grotere kopie van de installatie van Enerkem in Canada. Beide zijn bestaande technologieën. Het is een bestaand project met een aanpassing om de eindmarkt zekerder te maken.”

‘Enkele tientallen kilotonnen’

Behalve vliegtuigbrandstof zal de installatie ook nafta gaan maken. “De verhouding vliegtuigbrandstof/nafta komt op ongeveer 70/30 te liggen”, stelt Boon. De fabriek krijgt volgens hem een capaciteit van ‘enkele tientallen kilotonnen’ vliegtuigbrandstof en nafta per jaar.

Locatie

Een definitieve keuze voor de plek waar de fabriek komt, is nog niet genomen. “We onderzoeken wat de beste locatie is. Daarbij houden wij rekening met de benodigde infrastructuur, de grondstoffen die binnenkomen en de fysieke ruimte die nodig is. Er zijn verschillende opties”, vertelt Van Dooren. Zit Shell Pernis daar ook bij? Boon: “We kijken naar Shell Pernis, maar ook breder in de Rotterdamse haven.”

Verandering consortium

De wijziging heeft ook tot gevolg dat het consortium een verandering ondergaat. “Dit is een logisch punt voor partijen om zich de vraag te stellen of het zinvol is door te gaan. Voor twee bedrijven is dat veranderd. Het project gaat door met Enerkem, Shell en het Havenbedrijf Rotterdam. Nobian [voorheen Nouryon, red.] en Air Liquide blijven het project steunen, maar maken geen deel meer uit van het consortium”, zegt Van Dooren. Er moeten opnieuw vergunningen worden aangevraagd, wat begin volgend jaar gaat gebeuren. Eind 2022 moet de investeringsbeslissing worden genomen. “Ons doel is de fabriek in 2025 of 2026 in bedrijf te nemen”, aldus Boon.

Deelnemers Waste-to-Chemicals

- Air Liquide

- Enerkem

- Havenbedrijf Rotterdam

- Nobian

- Shell

Deelnemers Waste-to-Jet

- Enerkem

- Havenbedrijf Rotterdam

- Shell

Zie ook: Shell voegt zich bij waste-to-chemicals-consortium

English translation

Waste-to-chemicals becomes waste-to-jet

Sustainable aviation fuel

The ‘waste-to-chemicals’ project in Rotterdam is taking a new direction. The planned plant will not produce sustainable methanol, but sustainable aviation fuel. A reactor section in the plant’s design will be replaced for this purpose. The consortium continues with Enerkem, Shell and the Port of Rotterdam Authority as participants. “The market for aviation fuels is relatively more secure and better for this project. So less risky.”

In October 2016, a consortium [see below, ed.] presented the plan to build a ‘waste-to-chemicals’ plant in Rotterdam, which would produce sustainable methanol from waste. “We have used the past few years to make the business case more robust and to develop it further”, says Nico van Dooren, director of new business development at the Port of Rotterdam Authority, one of the participants in the consortium. “The role of the partners was examined, as well as the most optimal location of the plant and the required infrastructure. At the same time, the development of the technology continued and the business case was further analysed.”

‘Green infrastructure’

Shell joined the waste-to-chemicals consortium in 2019. “Shell’s objective is to decarbonise the entire business”, explains Andries Boon, team leader at Shell for biofuels development in Europe. “Moreover, infrastructure such as Porthos, the heat grid, electrolysers and the hydrogen backbone offer synergy with this kind of project. After all, we need electricity and hydrogen, and we produce CO2. So it is an advantage to be able to connect to green infrastructure. That possibility makes the Rotterdam industrial cluster attractive to us.”

Change of course

Now it appears that a major change of course is underway. “We have held the project up to the light”, says Boon. “Eighty to ninety per cent looks good. Only the market for methanol is comparatively shallower. It is difficult to base a first project on that. Furthermore, the application of sustainable methanol in biochemistry is less encouraged by the current regulations.”

Waste-to-Jet

Instead of methanol, the plant will produce sustainable aviation fuel. Boon: “Waste is the perfect raw material for making aviation fuel in the long term. There are few alternatives. Airplanes are not likely to fly on hydrogen or electricity. You are therefore stuck with a liquid as fuel. Waste is an excellent raw material for this. It allows you to create a sustainable business case for the long term. The aviation industry is in the spotlight to decarbonise. We are helping airlines and airports to reduce their carbon footprint. For us it is a safe market for a first plant with quite a lot of risk.”

Chain of carbons

The turnaround mainly concerns the sales market, and to a lesser extent the design of the plant, Van Dooren and Boon emphasise. “Eighty percent of the plant remains the same”, Boon explains. “We break down waste streams such as food, wood and plastic packaging material into syngas, which consists of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. That is the same as originally planned. But we don’t simply attach the carbon monoxide to hydrogen in one go to make methanol, but we string it together in a longer chain of carbons. That is a typical aircraft fuel. A reactor is installed at the back of the plant for this purpose. Shell has been using this Gas-to-Liquid technology for decades. In Malaysia and Qatar, it is used on a large scale.” According to Boon, you cannot speak of a completely new concept. “Eighty per cent of the plant is a larger copy of the Enerkem plant in Canada. Both are existing technologies. It is an existing project with a modification to make the end market more secure.”

‘Several tens of kilotons’

Apart from jet fuel, the plant will also make naphtha. “The ratio of jet fuel to naphtha will be about 70/30,” says Boon. According to him, the plant will have a capacity of ‘several tens of kilotons’ of aviation fuel and naphtha per year.

Location

A definitive choice for the location of the factory has not yet been made. “We are investigating what the best location is. We are taking into account the necessary infrastructure, the raw materials that come in and the physical space that is needed. There are various options,” says Van Dooren. Is Shell Pernis one of them? Boon: “We are looking at Shell Pernis, but also more broadly in the port of Rotterdam.”

Changing consortium

The change also means that the consortium is undergoing a change. “This is a logical point for parties to ask themselves whether it makes sense to continue. This has changed for two companies. The project continues with Enerkem, Shell and the Port of Rotterdam Authority. Nobian [formerly Nouryon, ed.] and Air Liquide continue to support the project, but are no longer part of the consortium”, says Van Dooren. Permits must be applied for again, which will happen early next year. The investment decision must be made by the end of 2022. “Our goal is to have the plant operational in 2025 or 2026,” says Boon.

Participants Waste-to-Chemicals

- Air Liquide

- Enerkem

- Port of Rotterdam Authority

- Nobian

- Shell

Participants Waste-to-Jet

- Enerkem

- Havenbedrijf Rotterdam

- Shell